War reporting is extremely dangerous, addictive and taxing.

Never has it been more perilous for foreign correspondents in war zones, with 2024 being the deadliest year for media personnel in conflict zones.

Edith Dickenson, Iris Dexter, Dorothy Drain. Just some of the incredible Australian female war correspondents whose names you may not recognise, but who challenged traditional gender roles, defied government restrictions and stood resolute against workplace discrimination to get close to the action.

Many of the women featured not only faced exclusion from the ‘boys club’, they also risked their lives to capture history as it happened. Despite being relegated to the sidelines, reporting from places such as military hospitals and bases rather than front lines, these women found ways to subvert rules and gain access to unique stories in their pursuit for equality and recognition.

Edith Dickenson

Portrait of Edith Dickenson, 1900. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Edith Dickenson was Australia’s second female war correspondent, reporting on the Boer War only months after nurse and fellow journalist, Agnes Macready. Edith had a distinctive journalistic approach and scandalous personal life. Born in 1851 into England’s aristocratic society, Edith left her husband to live with her lover, Dr Augustus Dickenson. Initially settling in Tasmania, they frequently moved around Australia’s colonies.

In 1900, Edith travelled to South Africa to cover the war for the Adelaide Advertiser. Despite her gender, her correspondent’s pass and influential connections allowed her to travel through Transvaal, Natal and the Orange Free State gathering stories and interviewing civilians. Edith was specifically sent to capture the ‘women’s angle’, a recurring trend for female reporters. Whilst her articles were initially pro-imperialist, she became critical after gaining access to British-run concentration camps. Sickness was rampant and food and water were scarce; approximately 26,000 Boer women and children died in camps. Edith’s empathetic and frank articles stand out amongst the otherwise pro-colonialist reports, establishing a place for other future female correspondents to challenge the status quo.

Louise Mack

Portrait of Louise Mack. Photograph by Kerry and Co. Bibliographic ID: 1605015. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

Louise Mack was an avid poet, novelist and one of few female war correspondents during the First World War.

Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War had banned correspondents accessing the Western Front. Yet, Louise’s memoir tells a daring story of her witnessing Germany’s invasion of Belgium. Louise took shelter in a hotel with other correspondents during the invasion, purportedly escaping by posing as a mute hotel maid. She fled to England using a fake passport and published articles in the Daily Mail and The Sphere.

Louise’s story became mythic. After returning to Australia, she spoke at public lectures attracting large crowds and published a memoir. She featured embellished and contradictory details; likely to overstate her proximity to the invasion. Whilst controversial and captivating, Louise remains a pioneer.

Iris Dexter

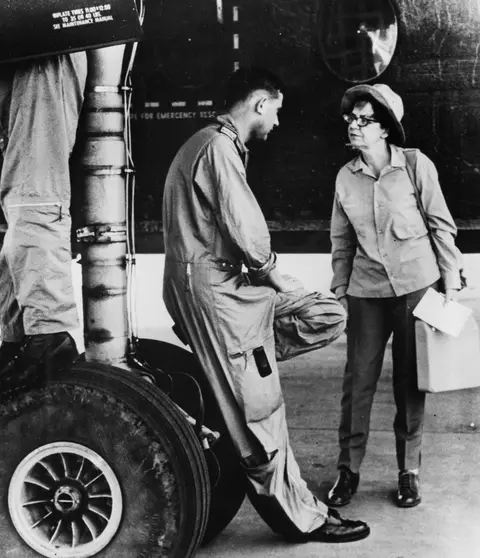

Iris Dexter standing under the starboard engine of a Doughlas C-47 aircraft. Photograph by Barbara Isaacson.

Iris Dexter was an enigmatic trailblazer whose witty articles and stylish appearance set her apart. She was Woman magazine’s senior reporter, with two feature articles. One for serious news, the other a humour column under the pseudonym ‘Margot Parker’.

After months of campaigning for licences, Iris and seven other Australian female journalists travelled throughout NSW and QLD as official war correspondents. All articles were censored by the Department of Information (DOI) and published under the condition they made the women’s home front effort appear glamourous.

To stand out amongst the other journalists, Iris wrote profiles of strong females who were vital to the women’s military services. For her humour column, Iris adopted the character Frenzia Frisby to write subversive, ironic articles that poked fun at her colleagues needing their ‘creature comforts’ in the Australian bush.

Iris was finally allowed into South-East Asia a month after Japan’s surrender. Iris reported on the repatriation of prisoners of war but was not technically in an operational war zone and was not classed as an official war correspondent. Whilst her articles pushed the boundaries, Iris’s relegation to the periphery reflects the experiences of many female journalists.

Lorraine Stumm

War correspondent Lorraine Stumm with Gary Cooper, Brisbane, 16 November 1943. Photograph by Queensland Newspapers Pty. Ltd. Courtesy of the State Library of Queensland.

Raised in Australia, Lorraine Stumm moved to the United Kingdom in 1936 and was hired by the London Daily Mirror. She and her husband Wing Commander Harley Stumm were forced to evacuate from Singapore to Australia in January 1942.

Keen to continue reporting on the war, Stumm constantly contacted the DOI, applying for permission to travel to active conflict zones. After staunch refusals, Lorraine took matters into her own hands, gaining permission from American General Douglas MacArthur to travel to New Guinea. However, she was not allowed close to the front lines.

Later, Lorraine was flown over the bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She recalled being silenced by the devastation but was unable to tell her colleagues for fear of being seen as “too emotionally fragile” to be a war reporter. She was the first to interview a European survivor of the bombing.

Lorraine’s ambition and unique status as a British and Australia reporter ultimately enabled her to get closer to combat than many of her predecessors.

Dorothy Drain

Australian war correspondent, Dorothy Drain representing the Australian Women’s Weekly, speaking with RAAF Caribou flight crew at an air base during the Vietnam War. Photographer unknown.

Dorothy Drain had an impressive 38-year career as a journalist and war correspondent. Dorothy worked for the Australian Woman’s Weekly, rising through the ranks to become its chief editor in 1972.

Insightful, serious and determined to provide women with hard-hitting war stories, Dorothy didn’t let obstacles such as a lack of female facilities or government restrictions stop her during the Second World War.

Like Stumm, Dorothy visited Hiroshima and after witnessing the devastation, she became decidedly anti-war and emphasised its futility. Despite this, Drain covered many conflicts including the British Commonwealth Occupation Force, Malayan Emergency, Korean War and Vietnam War, focusing on the effect on women.

Dorothy retired in 1975. Her incredible career created a legacy for future female war journalists, proving their worthiness and capabilities.

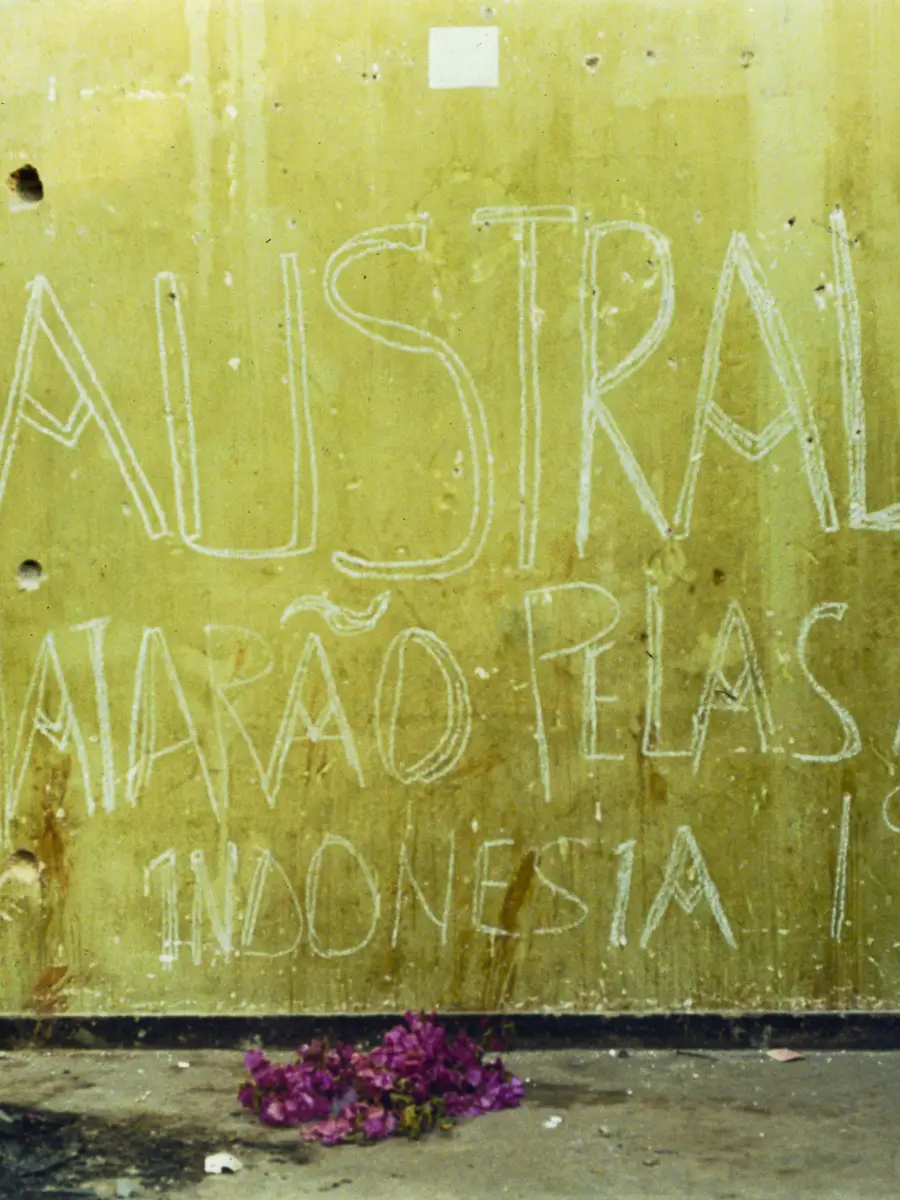

Ginny Stein

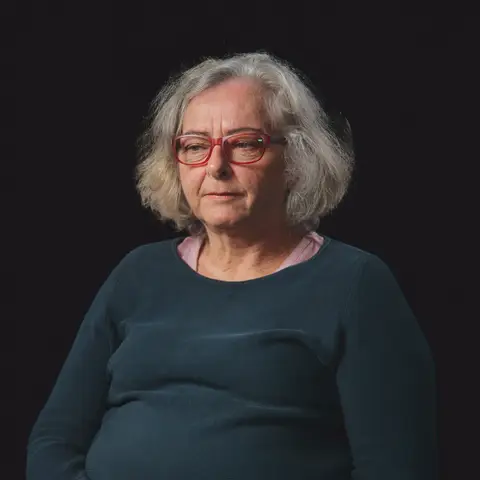

Virginia ‘Ginny’ Stein being interviewed for the Australian War Memorial exhibition Action! Film and War. Produced by Aquilo Productions. AWM2022.1134.13 [film still]

Ginny Stein worked as a foreign correspondent for the ABC and SBS, covering wars and civil unrest. As one of Australia’s first female video journalists, Ginny risked her life travelling to countries such as East Timor, Sudan, Afghanistan, Somalia and Zimbabwe.

She covered seminal moments of world history including the end of the Khmer Rouge regime and the overthrow of Indonesian dictator Suharto. Starting her foreign correspondent career in South-East Asia, Ginny recalled learning how to operate a video camera from colleagues.

Although wages were equal and journalism had become a more viable career path for women upon her return to Australia in the late 1990s, Ginny experienced hostility, suspicion, disdain and a lack of care for her wellbeing from management figures in her newsroom.

She currently works as a freelance journalist with a focus on world news, disaster relief and telling personal stories.

Sally Sara

Sally Sara in Kabul during her posting to Afghanistan from February to December 2011. Photograph by Sally Sara.

A modern, experienced and tenacious foreign correspondent for the ABC, Sally Sara reported from over 40 countries including Afghanistan in 2011.

Whilst in Afghanistan, Sally featured the voices of many women and children, focusing on the civilian impacts of the war. She, like other trailblazing female reporters, featured individuals to tell complex stories and communicate the often incomprehensible. Sally, unlike her male counterparts, was able to speak to women under the country’s strict civic and religious rules. She reported from a combat hospital at Kandahar Air Base, filming the extreme toll of the war on civilians and saw their injuries firsthand.

From Australia, Sally also reported on the difficulties of veterans returning from deployment and the high rates of PTSD. Sally also suffered the effects of trauma after her assignment in Afghanistan, later writing a play called Stop Girl based on her experiences.