On 16 October 1975, five Australian based journalists were killed by Indonesian military forces in Balibo, East Timor.

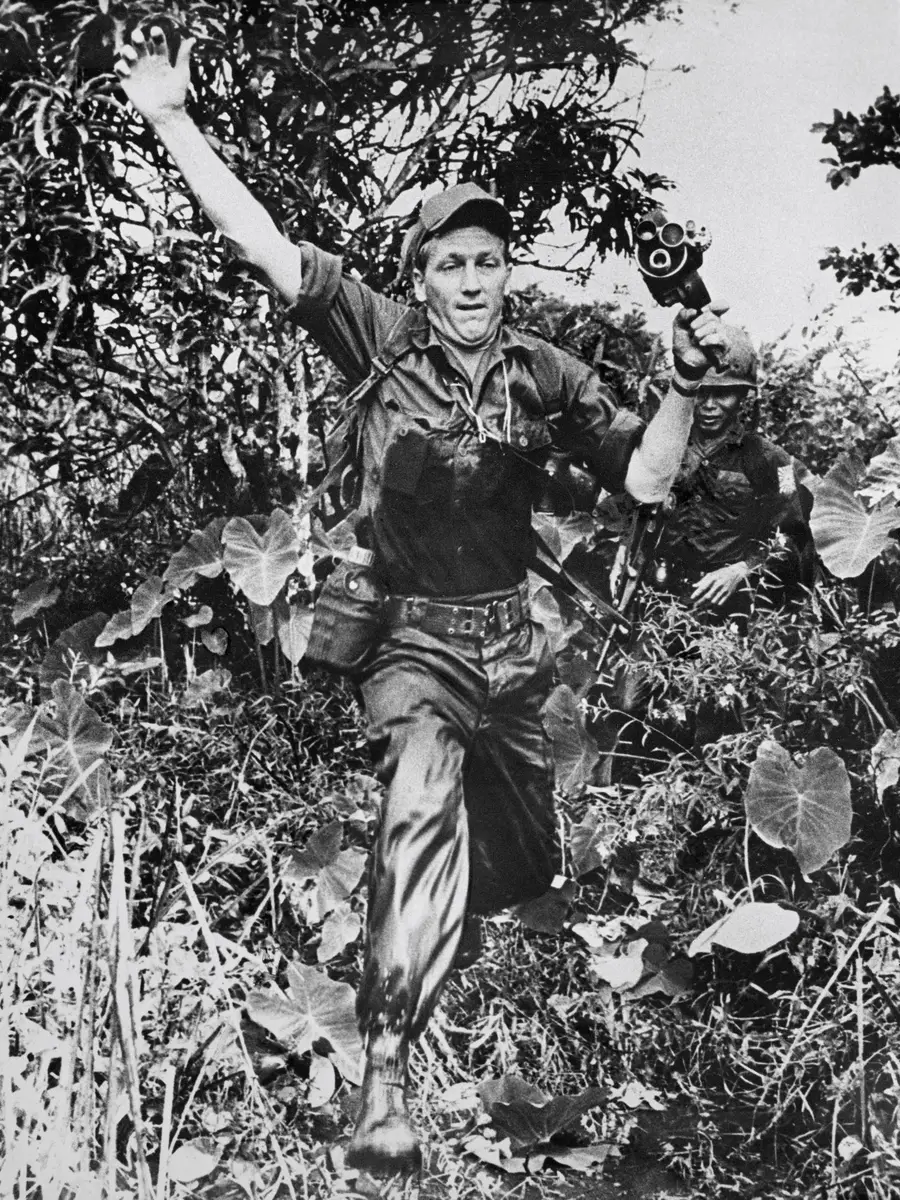

The Balibo 5 – reporter Greg Shackleton (29), sound recordist Tony Stewart (21), and New Zealand cameraman Gary Cunningham (27) with HSV-7 (now Channel 7), and Britons Malcolm Rennie (29) and Brian Peters (24) with Channel 9 – were investigating and reporting on military incursions near the border and the pending Indonesian invasion into Portuguese Timor.

In the last known report from Greg Shackleton, he begins “something happened here last night that moved us very deeply”, before outlining how he had spent the night in a small unnamed village and faced a “barrage of questioning from men who know they may die tomorrow and cannot understand why the rest of the world does not care” (Channel 7 footage).

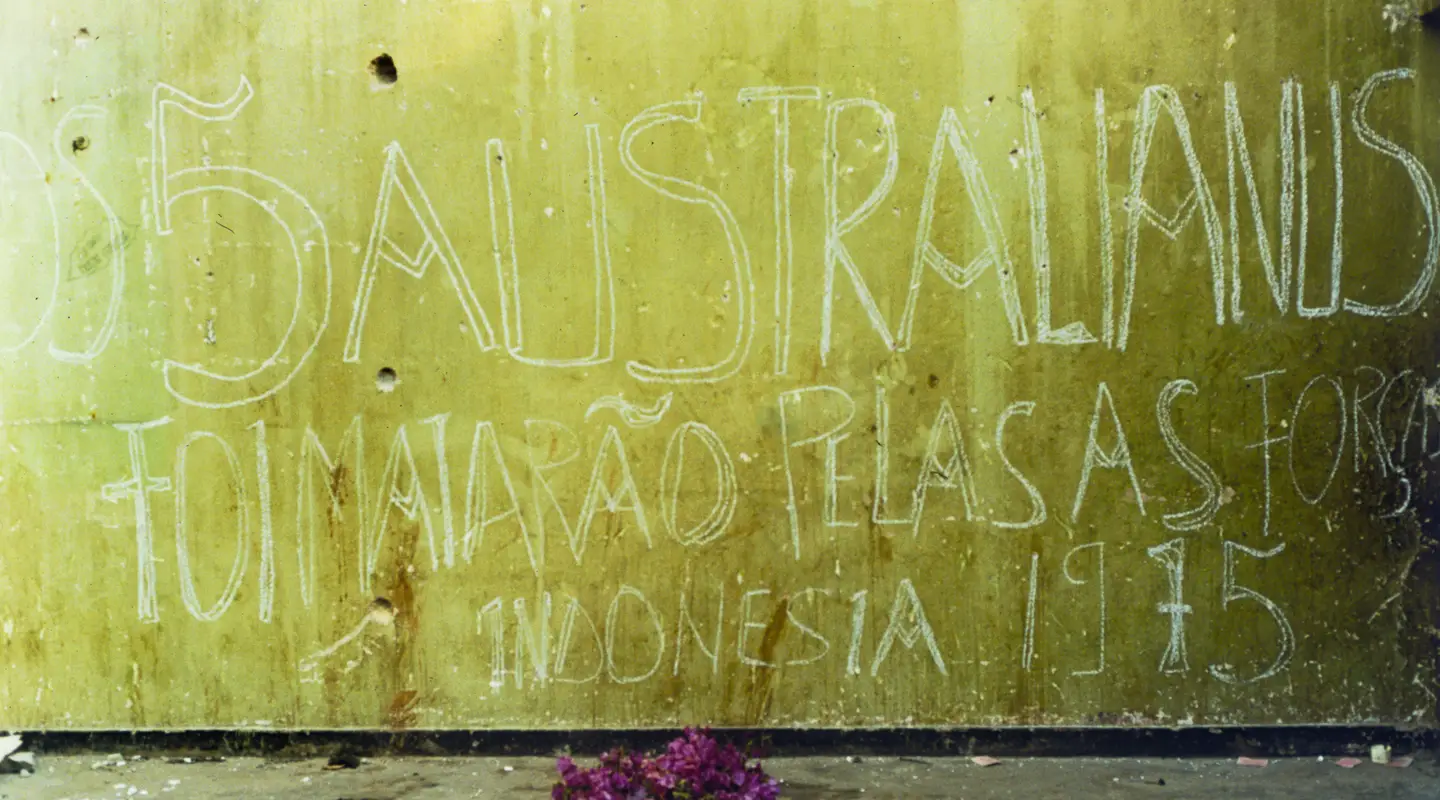

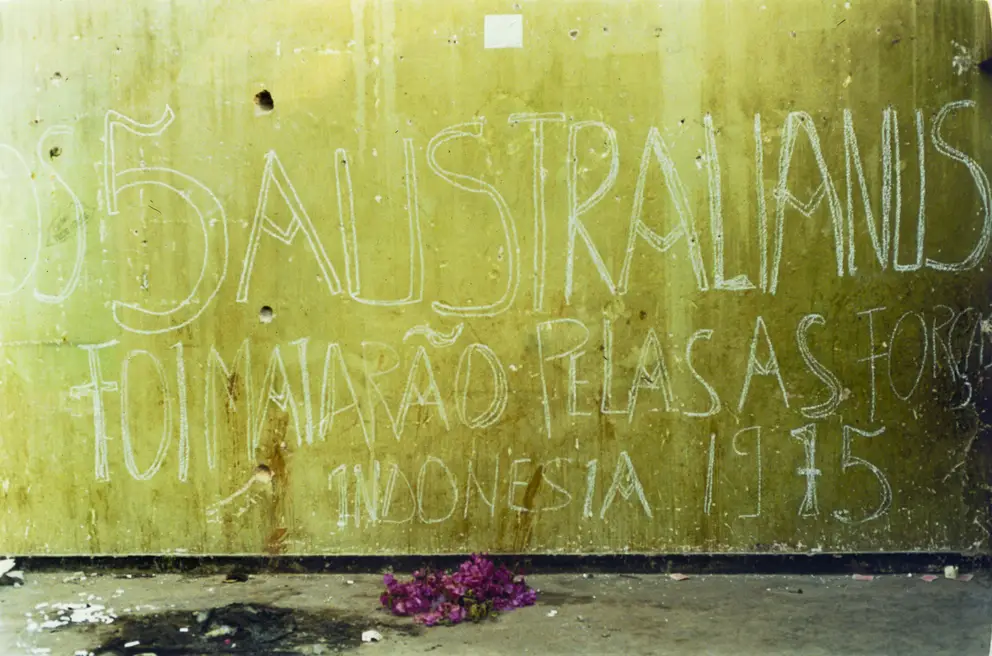

A 1999 memorial to the Balibo 5. Photographer: Christopher Barham. P03408.005

In a 1978 interview, Shirley Shackleton, recalled talking to her husband about his assignment and his reasons for going to East Timor. “He’d been following the story, that the Timorese had been asking for help and that the Indonesians kept insisting that they weren’t there, and he was getting very angry. He wanted to know exactly what was going on, especially since it’s so close to Australia. He felt it was very important to know what was happening … and he wanted to get the truth”.

The house where the Balibo 5 were staying. The paint has since been removed. Photographer: Christopher Barham.

It is often assumed that it was this journalistic desire for truth and for the world to know, that led the five men to stay in Balibo as the invasion became imminent. As unarmed civilians and Australian journalists, it is likely that they believed that they would not be targeted, even as the local people fled the area. To identify themselves, a large red “AUSTRALIA” sign and an Australian flag was painted on the outside of the building in which they were staying.

Early in the morning on 16 October, the Indonesian forces attacked Balibo, and the five journalists were killed. Exact details remain uncertain and contested. Some reports suggested that they had been caught in the crossfire, while others testified that they had been deliberately executed.

Initially, the five men were reported missing.

“I got a phone call from Channel 7 to say they were missing, and when I heard that on the phone, I thought straight away, no they’re not missing, they’re dead.”

Shirley Shackleton

Others had the same intimation as to their fate. Roger East, another Australian journalist travelled to East Timor to investigate, however, he was also reportedly executed by the Indonesian military in Dili. In early December 1975, Indonesian officials confirmed the death of the Balibo 5 and handed over fragments of burnt human remains and some personal effects to the Australian Embassy in Jakarta.

The house in which the Balibo 5 were killed. Photographer: Rick Amor.

At the time, and in the five decades since, the fate of the Balibo 5 (and Roger East) has caused outrage and controversy in the Australian media and public opinion. Many questions have been raised about the circumstances of their deaths and those ultimately responsible. There have been several investigations, including a 2007 NSW coronial inquiry which determined that the Balibo 5 were “shot and/or stabbed deliberately, and not in the heat of battle, by members of the Indonesian Special Forces”. The response of several successive Australian Governments (or lack thereof) has also been heavily criticised, particularly that no formal complaint was ever sent to the Indonesian government, and no-one has ever been charged with their murder.

While no footage or news reports remained to tell the world of the Indonesian invasion, the death of the Balibo 5 ultimately achieved what the men had set out to do – raise awareness and interest in the conflict in East Timor amongst the Australian media and wider population. As well as increased media coverage and public interest, the whole affair also created an enduring legacy and shared history between the two countries that continues, particularly as we remember the Balibo 5 fifty years on.

Wreath laid at the War Correspondents Memorial Ceremony in honour of the Balibo 5. Photographer: Marcus Fillinger.

Interview with Greg Shackelton's wife Shirley who recalls talking about his assignment and learning of his death.

Did you discuss with Greg before he went why he was going up there?

Yes, in quite some detail because it seemed to me that it was very dangerous to be going. I think probably the best way is to just tell you what he said to me. If he refused an assignment, what would be the use of him to any other firm that he ever worked for or to the Herald? He also had been following the pleas for help from the Timorese for some weeks and he really was getting angry and wanted to know what was going on because the Indonesians kept insisting that they weren't there. And he thought it was time someone went over and found out. There was another aspect to it too. I've forgotten what it was sorry.

Roll 2, slate 2, interview with Shirley Shackleton.

What was the reasons that Greg went over to Timor?

Well, he'd been following the story that the Timorese were asking for help and that the Indonesians kept insisting that they weren't there and he was getting very angry. He wanted to know exactly what was going on. Especially since it's so close to Australia, he felt it was very important to know what was happening.

So he wanted to get the truth.

And he wanted to get the truth, yes.

Any other reason?

Well, I think all journalists want to get well known. You know, the better known you are, the more interesting jobs you'll get. And he was about to go to America and I think he felt that that would give him a much better chance to get good work in America if he'd done that sort of work.

Some of the other journalists that I've talked to, they talk about an adrenaline rush. They like to be where the action was. Was that in Greg's nature too?

Well, he loved to do a good job, but I don't think that would be... I think that's too simplistic to say. Obviously, if you're doing a good job and you're working in something exciting, you get a great kick out of it. You know you're doing well. But I think that's too simplistic for him.

Did you discuss it with him before he went, why he was going and what the possibilities were?

Yes, we discussed it in detail because I thought it was so dangerous. And naturally, I wanted to know why was he going. And he gave me the reasons I've just given you. And I remember saying to him, but surely it's so dangerous, why are you going? And he said, oh, come on, be realistic. If I start to refuse assignments like this on the grounds that they're dangerous, I might as well give up the work.

Do you think a wife should put pressure on her husband if he's a journalist or cameraman not to go, if he's a married man with a child?

I don't think a wife should put pressure on her husband for anything. Whether it's to immigrate to another country and she doesn't want to go, I think she should go. Either that or not get married at all. People should do what they want to do, not what someone else thinks they should do.

What was going through your mind while Greg was away?

Well, I thought that it's very likely we'd never see him again.

You actually had that premonition, did you?

No, it wasn't a premonition. I mean, if someone goes into a war zone, they're going into a dangerous area where they're likely to be hurt or killed. And I think I'm very practical. It was in my mind that probably something might happen to him. It must be a fear that anybody has if somebody's... I mean, my little boy had a paper round recently. And it was in my mind that he might get knocked over by a car when he was going over to sell the newspaper. I didn't stop him from going to do that, but I was very worried the whole time he was gone.

Was he missing long before you learned of his death?

Some hours, I suppose. My mother-in-law rang me to say that she'd heard a newscast on the ABC that the journalists were missing. And she was rather angry about that because no one had let her know. But, of course, no one else knew at that point. It had just come through Reuters, I suppose. And next, I got a phone call from Channel 7 to say they were missing. And when I heard that on the phone, I thought straight away, no, they're not missing. They're dead. It wasn't, again, it's putting too much to say it was a premonition. I just felt, no, and they'd been dead for some time.

How did you learn, finally, that they were dead?

We have never learned that they were dead. There have never been any bodies, and there's never been any admission from the Indonesians that they were killed. All we've got is supposition. The Australian government, since those people have never walked back to Australia, have to assume that they were dead. Even when we asked for positive identification of some bones, the bones that were sent to Jakarta for that identification, the doctor who had to do that said the most he could say about them was that they were possibly human.

Do you believe that he's dead nevertheless, given all the facts that have been presented to you?

Yes, he must be dead, because somehow or other a message would have come through. But the awful thing about not having the body to lay the ghost, as it were, is that you always go on wondering, I wonder if he might be in, I mean, if I read in the paper that someone's turned up after 20 years, I think, oh, wouldn't that be terrible if that was Greg, if he was up in a camp now with the Indonesians? It's possible, but highly unlikely.

What do you think of the proposition that some journalists or cameramen go into a war zone with a latent death wish?

Yes, I think that's possible. But I'm not your friendly neighbourhood psychologist. I can't really go into that too deeply. But it is interesting that Greg had always thought that he would die very young. I don't think for one minute he remembered that when he went up there. I'm sure of it, in fact, because I think we would have discussed it. He would have mentioned it to me. He was just ready to go. Greg knew at last exactly what he wanted to do. He was off to America very shortly. He was due to go to America. He was going to do a course at Columbia University run by Fred Friendly, who was the man behind Ed Murrow. It was because of Fred Friendly backing him as a producer that Ed Murrow was able to do what he did. And that man runs the course at Columbia University.

Can you just discuss for me the context in which Greg talked about, or you talked about, sticking up his head and the possibility of getting shot?

He said to me, look, if I'm not back within a couple of weeks, the possibilities are that I'll either be shot from putting my head up at the wrong moment, or I'll be taken prisoner of war, or by far the thing that frightened him most, and he was very, very nervous about, not nervous, but very aware of the danger in going, was that they might get lost. And it worried him greatly that they didn't have proper maps of the terrain, nor did they know very much about it. Neither had any of them ever had any bush experience of surviving in the bush. And that, I think, was the possibility that worried him most. It never occurred to him he'd get killed. That's why I'm sure that he didn't have a latent death wish, even though for years he'd felt that he wouldn't live to be an old man.

You still haven't answered for me satisfactorily what was going through your mind at the time while he was away.

Well, I was afraid that something would happen to him.

How did you accommodate that, though, in terms of what you were doing and working? Did you try and put it out of your mind?

You have to keep working and put it out of your mind. See, I've been just as worried about Greg when he's had to do things around here, if I've known that there was a building that was burning, and he was going to report the story. I've been just as worried, waiting for him to come home, from that. There have been a couple of things. There was a ship on fire somewhere, and he had to drive down late at night, alone in a car, do the story, and then drive all the way back to Melbourne with the film and everything in the car. Now, that was a very dangerous thing that he had to do because of the driving back, strange enough, and I was very worried about that, too.

What do you do? You try and divorce it from your mind, make yourself busy?

Yeah, and if you've got children, I've got a little boy. I think you're very lucky if you've got a child because you go on with your life normally for the sake of the child, and you don't go into a heap in the floor and think, Oh, my God, he's never going to come back. It was just on my mind all the time. Like, I suppose, in a way, it's on my mind all the time that perhaps he's not dead and that he might turn up one day. Actually, I hope he is dead. He's much better off dead than in a prisoner-of-war camp. It would be terrible to think of someone like that who knew exactly what he wanted to do, being chained up or beaten or starved or anything.

Cut.