Eavesdropping on German prisoners in England provided crucial intelligence.

As German tanks rolled into Poland on 1 September 1939, one of Britain’s most senior MI6 intelligence officers, Thomas Joseph Kendrick, arrived at the Tower of London. Over the centuries, the thousand-year-old fortress had seen many famous prisoners, including British royalty. At the beginning of the Second World War it was about to receive German prisoners of war. Within a special area at the rear of the tower, overlooking Tower Bridge, away from the public eye, Kendrick opened a unit that would bug the conversations of German prisoners in their rooms. After a phoney interrogation, the prisoners returned to their comrades and boasted about what they had not told the interrogators. In these early days, the prisoners were mainly U-boat crews who believed that the British were stupid and incompetent at interrogation. Little did they realise that the light fittings and thick stone fireplaces in the tower had hidden microphones, wired back to an M (meaning ‘miked’) room where secret listeners recorded their conversations.

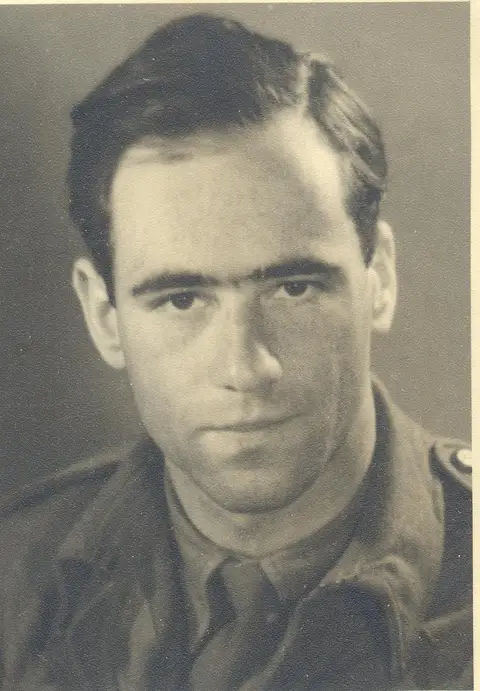

Colonel Thomas Joseph Kendrick headed the eavesdropping operations.

An RCA microphone, one of many secreted about the grounds of Trent Park. Image courtesy of Helen Fry.

By the end of September 1939, Kendrick already had 60 German prisoners in the tower. Captured German air force pilots and crews soon began to arrive, and spoke to each other about their war, tactics, new German technology and the unbreakable Enigma codes. As Kendrick’s small team of army, air and naval intelligence officers gathered snippets of information, it became clear that this method of surreptitiously gaining intelligence from German prisoners was remarkably effective.

Kendrick requisitioned the country estate of Trent Park on the northern edge of London at the end of the Piccadilly Line of the Underground. His team moved into the house to wire it for sound and under the auspices of a new branch of military intelligence – MI9 – relocated there by the end of 1939. Kendrick increased his personnel to 500, a third of whom were women.

Trent Park

Trent Park, North London. The scene of some of the Allies’ biggest intelligence coups. Image courtesy of Helen Fry.

The house swiftly became a massive intelligence gathering factory that provided information to codebreakers and cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park, as well as to MI5, MI6 and military commanders. More than 3,000 German and Italian prisoners of war came through Trent Park between 1940 and 1942. The volume of intelligence that they gave up to the hidden microphones was staggering: information relating to the upcoming Battle of Britain, new enemy technology, night fighter strategy, new aircraft and fighting capability, U-boat operations and construction, German campaigns on the Russian front, detailed information on coastal defences, enemy operations ahead of D-Day and the Ardennes campaign, and details of mass atrocities and concentration camps.

Within two weeks of the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, American intelligence officers from the Office for Strategic Services (OSS) began to arrive at Trent Park. They went on to make a valuable contribution as interrogators and intelligence officers, marking the beginnings of Anglo-American intelligence cooperation that continues today.

The information amassed was so significant that Kendrick expanded his clandestine unit further in 1941 to cope with an anticipated influx of thousands of prisoners from future campaigns. He requisitioned two country estates about 20 miles from London: Latimer House and Wilton Park in Buckinghamshire. Reserved for lower rank German prisoners of war, these sites went on to process more than 10,000 prisoners of war. In the M rooms, teams of secret listeners recorded their unguarded conversations.

The listeners were German–Jewish refugees who had fled to avoid Nazi concentration camps and arrived in the United Kingdom before the outbreak of war. Working 12-hour shifts, every day of the year, these refugee men serving in British army uniform amassed tons of intelligence for the Allies. Émigré women transcribed and translated conversations which had been recorded on 78 rpm acetate discs. Female officers of the naval intelligence team conducted interrogations – becoming the first known female interrogators of the war – while other women carried out intelligence analysis of the material coming out of the M rooms across the three sites. This hidden workforce of men and women would go on to amass nearly 75,000 transcripts of bugged conversations during the war.

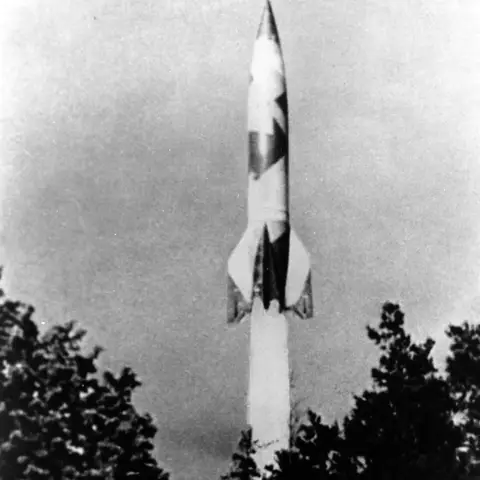

Intelligence proved the existence of Hitler’s secret weapon program at Peenemünde.

From 1942, Trent Park was reserved for the most prized prisoners of all: Hitler’s captured generals and commanders. The first to be captured was General Crüwell, seized in May 1942, followed by General von Thoma in November. By May 1943 General von Arnim had arrived at Trent Park with an entourage of senior officers and batmen from the battlefields of North Africa. After D-Day, high ranking German commanders – generals and two field marshals – arrived in stages. They were wined and dined, looked after by fake aristocrat “Lord Aberfeldy”, taken on trips to Simpsons on the Strand, and given copious supplies of gin at the Ritz. Kendrick had arranged for the house to be further wired for sound, with microphones embedded in the walls, under floorboards, behind fireplaces, in plant pots and the billiards table. Even the trees in the garden were bugged to record the generals on their walks around the grounds. The Mad Hatter’s tea party of daily life at Trent Park was recorded in weekly intelligence reports and transcribed conversations that preserve rare real conversations about the war and provide a unique snapshot of daily life during the Second World War.

The outlandish and frivolous treatment of the generals had one aim – to win the intelligence war. Giving 59 German generals and nearly 40 senior German officers a life of luxury in the mansion house arguably led to one of the greatest intelligence coups of the war. From the bugged conversations of Hitler’s most trusted commanders, the Allies gained the first concrete proof of Hitler’s secret weapon program at Peenemünde on the Baltic coast. This led to the bombing of Peenemünde in August 1943.

After the surrender of the Afrikakorps in May 1943, General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim and other senior officers were interned at Trent Park.

Intelligence gathered

Fritz Lustig, one of the secret listeners. Photo courtesy of Helen Fry.

From air force prisoners came information on the Battle of Britain, night fighter tactics, navigational methods, new kinds of aircraft, bombs and guns, advance information on the bombing of Coventry and Glasgow, and information on night radar appliances. It was estimated that reports from the air intelligence section covered “95 per cent of the whole developed and developing field of German radar and anti-radar devices with accuracy little short of 100 per cent”. This alone made a significant contribution to reducing Allied losses in night attacks over Germany.

Naval intelligence came in the form of information about U-boat types, personnel and tactics, the names of commanders, methods of attack, torpedoes, acoustics, mines (magnetic and acoustic), codes and naval Enigma machine, cyphers, gunnery, human torpedoes and details of the major units of the German navy. Information on the sinking of the fearsome battleships Bismarck, Scharnhorst and Tirpitz was provided by the survivors, all of whom came through Kendrick’s sites. The importance of this work was underlined by the Director of Naval intelligence, who wrote, “During five years of war, the interrogation of prisoners of war has been developed from an incidental source of intelligence to one of unique value. The Royal Navy and other services have become reliant on it.”

The bugging operation also provided detailed pictures of German tanks (new models and production) and rockets. They also acquired detailed information on the Gestapo, character studies of senior German commanders and their relationships with Hitler, orders of battle, and the state of the German fighting forces.

It was reported that Kendrick’s unit was “one of the most valuable sources of intelligence on [German] rockets, flying bombs, jet propelled aircraft and submarines”. The air intelligence unit working as part of Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre was able to report throughout the war on Germany’s research – chiefly flak rockets and guided projectiles, but also radio, radar and high frequency communications – often before they came into use.

“The worst job I ever carried out – which however I carried out with great consistency – was the liquidation of the Jews. I carried out this order down to the very last detail.”

General Choltitz, commander of Paris

There were dark conversations in which generals and other prisoners admitted to war crimes, atrocities in concentration camps and the murder of millions of Jews. General Choltitz, commander of Paris, confessed to General Thoma, “The worst job I ever carried out – which however I carried out with great consistency – was the liquidation of the Jews. I carried out this order down to the very last detail.” These unguarded conversations revealed that Germany’s military commanders knew about war crimes, and that some were complicit. These transcripts dispel the long-held view that the Wehrmacht played no part in the Holocaust.

It would be over 65 years before these secrets came out, when the files were released into the National Archives. By then, most of the intelligence officers and secret listeners had died without telling their families about the work they had done. They had signed the Official Secrets Acts and could not breathe a word to anyone. None of the secret eavesdroppers realised how their work had changed the landscape of the intelligence war, saving lives and affecting the outcome of the war.

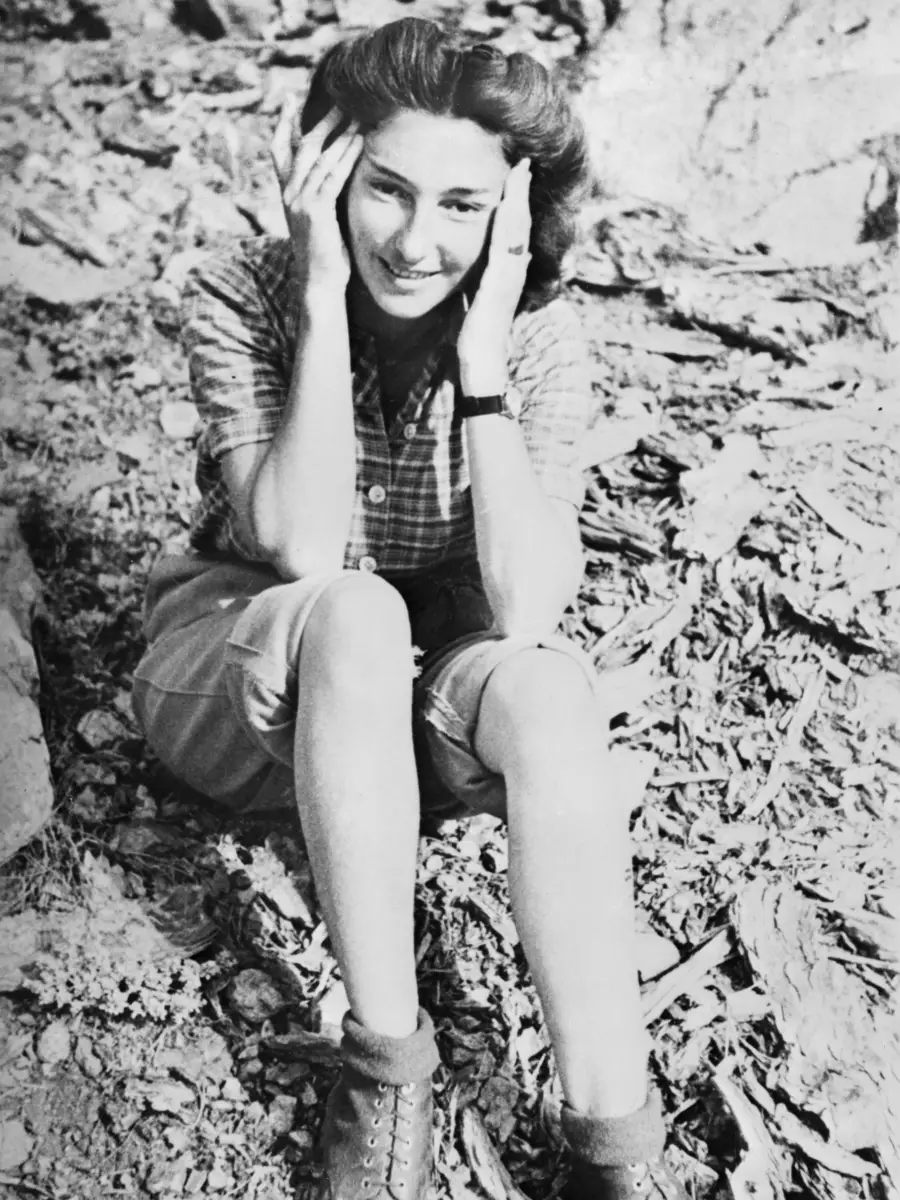

The Naval Intelligence Team outside Latimer House. The female officers became the first known female interrogators of the war. Photo courtesy of Helen Fry.

Forgotten legacy

The theatrical stage set that the generals walked into at Trent Park was one of the greatest deceptions against Nazi Germany of the Second World War. The magnitude of the achievements under Kendrick’s command is underlined in the words of his colleague, Australian-born Lieutenant Colonel Leo St Clare Grondona: “Had it not been for the information obtained at these centres, it could have been London and not Hiroshima which was devastated by the first atomic bomb.” All this was achieved without third degree methods (rough treatment or torture) at the M Room sites. Norman Crockatt, head of MI9 branch of Military Intelligence, wrote to Kendrick:

You have done a Herculean task, and I doubt if anyone else could have carried it through. It would be an impertinence were I to thank you for your contribution to the war effort up-to-date: a grateful country ought to do that, but I don’t suppose they will.

The Allied nations could not honour Kendrick publicly; Western Europe had entered a new war, the Cold War, in which similar techniques were being used.

Few people have heard of Thomas Joseph Kendrick, whose clandestine wartime sites provided pivotal intelligence and influenced the course of the war. He took these secrets to the grave, dying in 1972 at the age of 91. In February 2017, Historic England, the foremost national heritage body in the UK, concluded that the wartime work at Kendrick’s three sites was “of considerable national and international historical interest which bears comparison to the code-breaking work at Bletchley Park.”