Their achievements were remarkable, despite their earlier losses: but managing the alliance was not a simple matter.

For the British the Somme denotes a battle, but for the French it means a river and the département in northern France to which it gives its name. The French Army’s role in the 1916 battle of the Somme is neglected in France, where 1916 means the battle of Verdun.

That, the longest battle of the war (February to December 1916), involved only France and Germany. In the English language historiography, one might deduce that there were no French troops involved at all in the Somme battle. Yet, by the end of the battle, Britain and France had employed almost equal numbers of men, but the French gained more territory for little more than half the casualties.

The notion, still prevalent among English-speaking historians, that General Sir Douglas Haig was compelled to launch the battle earlier than he wished and in an area of France that he would not have chosen, must be discarded. The battle began on the date agreed the previous year, and in the sector agreed in February 1916. The timing and the theatre cannot be used as excuses for the failure to reach the objectives that were set for the battle.

Somme, August 1916. A deserted section of the battlefield at Deniécourt with a French soldier inspecting a dugout.

Indeed, the strategy for 1916 had been agreed at an allied conference at French headquarters in November 1915, when General Joseph Joffre was still French commander-in-chief and Sir John French was still his British counterpart. Attacks on all allied fronts were to take place as near simultaneously as possible, with the operation in France to encompass as wide a front as possible with a joint attack in which the new British armies would extend the line held by the French. On 14 February Joffre agreed with Sir John French’s successor, Haig, that the joint attack would take place where the armies met in Picardy and that the date would be around 1 July, after the weather and terrain had permitted the Russians and Italians to launch their own offensives.

General Maurice Balfourier, commander of XX Corps; with the map on his knees is General Emile Fayolle, commander of Sixth Army. These two French generals cooperated closely with General Henry Rawlinson’s Fourth Army, as XX Corps was in the front line next to the British XIII Corps. Illustrated War News, 9 August 1916.

As commander-in-chief, Joffre had to consider all the fronts in France as well as the Balkan front around Salonika; the day-to-day coordination of the Somme battle was given to General Ferdinand Foch, commander of France’s Northern Army Group. Since 1914 his task had been to ensure cooperation in Belgian, British and French operations in northern France. Haig knew Foch from the fighting around Ypres in October–November 1914, but the relationship was somewhat difficult because Haig preferred to deal with his counterpart, the French commander-in-chief, rather than the commander of an army group. Such a level of command did not exist in the British Army. Foch tried, however, to establish good relations between British General Headquarters and his own.

On 21 February, a week after the Joffre–Haig agreement, the German onslaught against Verdun began in eastern France. The citadel at Verdun and its ring of forts formed a salient in the front line, which enabled the German Fifth Army to make a concentrated attack on a region that the French would rush to defend. The German aim was to draw as many French troops to Verdun as possible, and to impose on them huge casualties, thereby destroying “Britain’s best sword”. When the anticipated British counter-offensive took place (so the Germans reasoned), Germany would face a weakened enemy and would prevail. Joffre’s response to the violent German attack at Verdun was, therefore, crucial in foiling this German strategy for victory.

“It is of prime importance to use the infantry with strict economy, only to ask of it an effort of which it is capable, and to direct it methodically and closely.”

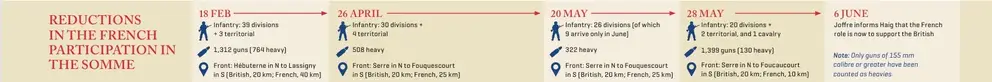

Joffre refused to abandon the agreed allied strategy for the 1916 campaign. He had allocated three armies to Foch, consisting of 39 infantry divisions plus three territorial divisions. The aim was to cross the Somme river, south of Péronne, supported by the British further north – a front of some 65 to 70 kilometres in all.

On 20 April Foch sent out a long document containing his “general directives” for Joffre’s operation. He emphasised a sustained and methodical artillery preparation, with the tasks for each calibre of gun listed. The infantry would attack only those positions destroyed by the artillery, but the artillery must then be moved forward quickly so as to fire on second and subsequent enemy lines. These directives reflected the lessons learned in the failed offensives of 1915, which had cost the French army huge casualties.

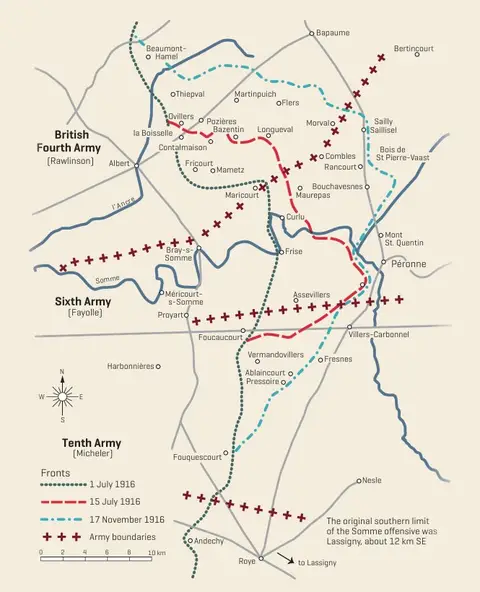

French Army fronts, July November 1916.

Although Germany’s initial spectacular gains in the opening days around Verdun had not been repeated, pressure began building there again in May as the German high command realised that preparations were being made for a Franco-British offensive. Because the politicians refused to abandon Verdun, Joffre was forced to send more men and guns there. As a result, the resources available to Foch for the Somme dwindled. Instead of 39 infantry divisions, supported by more than 1,300 guns, on 26 April he was promised 30 divisions but the number of heavy guns had been cut by more than a third. On 28 May the number of divisions fell once more to 20, supported by only 130 heavy guns.

Thus Foch now had about half the original number of infantry and, much more importantly, only about a sixth of the heavy artillery. The aim of the offensive changed: instead of the French forcing a passage across the Somme upriver from Péronne, supported by British troops on the northern bank, it became (on 6 June) French support of a British operation. Foch calculated the length of front he could attack with the guns now at his disposal and concluded that 15 kilometres was as much as he could handle. Haig, on the other hand, seems to have taken the allocation of the main role to the British Expeditionary Force as licence to expand his objectives. Foch was cutting his coat (his length of front) according to his cloth (his gun numbers); whereas Haig was obliging his Fourth Army commander to aim further and wider without reference to the number of available guns.

Reductions in the French participation in the Somme

Gradually units arrived from Verdun for the Somme operation, to be carried out by only one army – Sixth Army under General Emile Fayolle – rather than the three originally planned. By 3 June XX Corps was in line north of the river, and the two other Sixth Army corps south of the river were in place by the end of the month. Foch issued his final tactical notes on 20 June.

They emphasised:

- a strict minimum of troops in the first attack formation;

- infantry should attack only ground that the artillery has destroyed;

- units should be formed up in depth with brigade and divisional commanders placed so as to be able to communicate with each other.

His notes concluded: “It is of prime importance to use the infantry with strict economy, only to ask of it an effort of which it is capable, and to direct it methodically and closely.” Also, Foch placed great emphasis on aviation. The commander of the British Royal Flying Corps lost his bet that he would do better than the French: the French destroyed 13 German observation balloons on the first day, as against nine for the British.

A French 400-mm gun camouflaged. The French had more heavy guns than the British, an important factor in the greater success of the French.

When the infantry assault began on 1 July, the results of the first two days’ fighting in the French southern sector were most encouraging. Next to the British, XX Corps took all its objectives, carrying the German front line with very few casualties. South of the river, the I Colonial Corps did even better, capturing ground beyond the enemy’s first line. On the southern end of the line, XXXV Corps did less well, but this was the result of its exposed flank. French losses in Sixth Army were 3,300 for the first two days’ fighting, some 800 of them in XX Corps next to the British. There was a great disparity between the results achieved and the losses suffered in the respective British and French sectors.

When Haig insisted on reducing the length of the British front north of the Somme, the question arose of moving the main French effort to the south, where greater progress had been made. Some later claimed that a great opportunity had been missed by not doing so, but there were good reasons against such a shift. It would have meant moving the artillery in order to repeat the preparation that had made the initial success possible; there was no strategic ground to equal the German communications hub around Cambrai–Douai, the aim of the operation; the reserves of manpower were British, not French, and they were in the north. Consequently, XX Corps on the northern bank of the Somme was compelled to mark time until the British reached a line from which they could continue joint operations. The history of 11 Infantry Division, one of the XX Corps units, makes the point that it “lost the advantage of its magnificent advance on 1 July” and had to content itself merely with consolidating the captured German front line.

On Bastille Day, 14 July, the British Fourth Army’s night attack, which captured a large section of the German second position, brought the British to a line from which joint operations could resume. The French had been worried that the tactic of a night attack was too dangerous – in order to calm French fears, Fourth Army’s chief of staff had promised General Maurice Balfourier, commander of XX Corps, that he would eat his hat if it failed – but the weight and accuracy of the artillery bombardment had ensured success. The French had contributed significantly by ordering a substantial artillery barrage to support the British right in Trônes Wood.

It proved very difficult to resume such joint operations, for a variety of reasons. The weather was poor; the French north of the river were confined to a narrow sector between the river and the British; communications were difficult, with few roads and fewer bridges across the Somme and its marshy environs; agreeing start times required negotiation, as the British usually wanted to begin at first light whereas the French preferred to wait until the results of the preceding artillery action had been evaluated; firing joint artillery barrages was complicated by the French use of metres and the British yards. So the rest of July and all August passed in uncoordinated local actions.

The gun at the firing position at Ravin d’Harbonnières, Somme, 29 June 1916.

Joffre tried to force a return to a wide front coordinated attack like that of 1 July, but Haig would not be moved from his desire to wait for the tanks before doing so. At Verdun the pressure had eased, because the Russian offensive against the Austro Hungarians, which had begun on 4 June, had achieved initial successes. Now events on the Somme had contributed also, so that Joffre was able to commit a second French army (Tenth Army under the command of General Alfred Micheler), along with a considerable number of guns – 1,344 in total, of which slightly more than half (708) were heavies, plus another 64 extra heavy guns.

Joffre pressed Haig to attack at the end of August, and pressed again in early September, because he wished to coordinate action on the Somme with Romania’s entry into the war. Although the British operation with the new tank weapon began on 15 September, the French Sixth Army attacked three days earlier and captured Bouchavesnes on the Bapaume Péronne road. Tenth Army made its début earlier still, south of the river. Its artillery preparation began on 28 August at the same time as the Romanians advanced into Transylvania, and the infantry launched their assault on 4 September. The right hand corps captured its objectives easily but it proved difficult to make further progress, and it was only on 18 September that all the German strongholds in the southern sector were in French hands.

The September operations proved to be the last large-scale coordinated joint action. Mud dominated proceedings during October, although the fighting continued into November. Tenth Army made further progress in the south, completing on 7 November the capture of the two villages of Ablaincourt and Pressoire (the site of the modern high-speed train station). Sixth Army continued fighting northwards from Bouchavesnes along the road to Bapaume, reaching Sailly on 12 November. German machine-gun nests in St Pierre Waast wood to the east of the Péronne–Bapaume road prevented any further advance northwards. The huge French necropolis at Rancourt, just south of the wood, reveals the price the French paid for the road.

German first-aid station near the windmill in Le Transloy, on the road from Péronne to Bapaume. The windmill stood on a ridge in the third German defensive line. Reichsarchiv, Somme Nord, vol. 2 (1927).

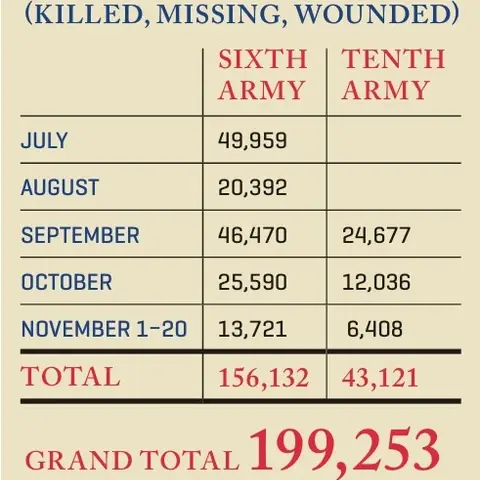

French casualties 1 July - 20 November 1916

At 202,000, however, French casualties were less than half those of the British. As a glance at the map shows, French territorial gains were slightly greater, albeit mainly in the less strategically important sector south of the Somme. By the end of the battle the French had contributed similar resources to those of the British: two armies (Sixth and Tenth) matching the British Fourth and Fifth. The 44 French infantry divisions making up 14 army corps within those two armies matched Britain’s 53 divisions in 11 corps.

When plans for the 1917 campaign were drawn up at French headquarters on 15 November 1916, it was no longer a question of a joint operation astride a river. There were to be separate British and French attacks against the large German salient in northern France. Joffre had succeeded in his refusal to allow Verdun to derail his Somme planning, but the results were insufficient. Both he and Foch were sacked.

Foch made a mournful entry in his notebook in April 1917. About the Somme, he wrote, “the British had set off in great numbers but with their inexperience had suffered huge losses; the French were fewer in number but captured more prisoners and guns.” Then he listed the results of the battle: “a German strategic withdrawal to the new Hindenburg defensive positions” and “a field marshal’s baton for Haig, but loss of command” for himself and for Joffre.